J.D. Vance, venture capitalist and author of Hillbilly Elegy, speaks on the American Dream and our Civilizational Crisis....

The Wisdom of Calvin Coolidge

President Calvin Coolidge served as president of the United States from 1923 to 1929. He oversaw one of the greatest periods of prosperity in American history.

Coolidge managed to bring the top tax rate on individual income down to 25 percent. But he never called for tax cuts without seeking matching budget cuts. When Coolidge left office, federal outlays were lower than they had been when he had taken office sixty-seven months earlier. And the federal debt had dropped by nearly one-third from its post–World War I high.

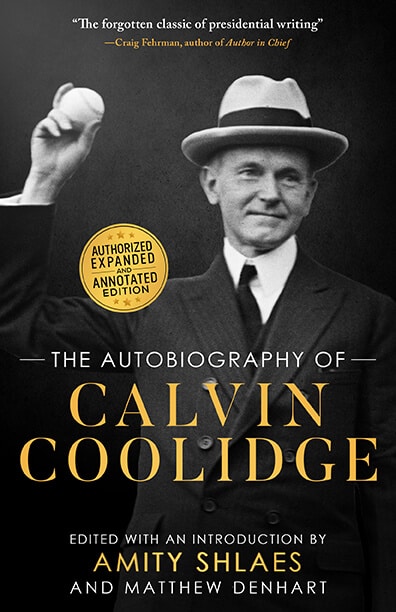

After he left the presidency, Coolidge published his autobiography. It is one of the great presidential memoirs. Presidential historian Craig Fehrman, author of Author of Chief, hails it as “the forgotten classic of presidential writing,” while the Wall Street Journal calls it the presidential memoir “that comes closest to literature.”

But literary quality is not the only reason we have produced a new, annotated, and expanded edition of The Autobiography of Calvin Coolidge. We have done so, also, because Coolidge offers much-needed wisdom for our age of exploding debt, increasingly centralized power, and fierce partisan division.

In this excerpt, Coolidge reflects on the principles that guided him upon assuming the Oval Office after the sudden death of President Warren Harding. As this passage makes clear, Calvin Coolidge is a model not merely of conservative governance but of character and humility as well.

—Amity Shlaes and Matthew Denhart

When the events of August, 1923, bestowed upon me the Presidential office, I felt at once that power had been given me to administer it. This was not any feeling of exclusiveness. While I felt qualified to serve, I was also well aware that there were many others who were better qualified. It would be my province to get the benefit of their opinions and advice. It is a great advantage to a President, and a major source of safety to the country, for him to know that he is not a great man. When a man begins to feel that he is the only one who can lead in this republic, he is guilty of treason to the spirit of our institutions. . . .

My fundamental idea of both private and public business came first from my father. He had the strong New England trait of great repugnance at seeing anything wasted. He was a generous and charitable man, but he regarded waste as a moral wrong.

Wealth comes from industry and from the hard experience of human toil. To dissipate it in waste and extravagance is disloyalty to humanity. This is by no means a doctrine of parsimony. Both men and nations should live in accordance with their means and devote their substance not only to productive industry, but to the creation of the various forms of beauty and the pursuit of culture which give adornments to the art of life.

When I became President it was perfectly apparent that the key by which the way could be opened to national progress was constructive economy. Only by the use of that policy could the high rates of taxation, which were retarding our development and prosperity, be diminished, and the enormous burden of our public debt be reduced.

Without impairing the efficient operation of all the functions of the government, I have steadily and without ceasing pressed on in that direction. This policy has encouraged enterprise, made possible the highest rate of wages which has ever existed, returned large profits, brought to the homes of the people the greatest economic benefits they ever enjoyed, and given to the country as a whole an unexampled era of prosperity. This well-being of my country has given me the chief satisfaction of my administration.

One of my most pleasant memories will be the friendly relations which I have always had with the representatives of the press in Washington. I shall always remember that at the conclusion of the first regular conference I held with them at the White House office they broke into hearty applause.

I suppose that in answering their questions I had been fortunate enough to tell them what they wanted to know in such a way that they could make use of it.

While there have been newspapers which supported me, of course there have been others which opposed me, but they have usually been fair. I shall always consider it the highest tribute to my administration that the opposition have based so little of their criticism on what I have really said and done.

I have often said that there was no cause for feeling disturbed at being misrepresented in the press. It would be only when they began to say things detrimental to me which were true that I should feel alarm.

Perhaps one of the reasons I have been a target for so little abuse is because I have tried to refrain from abusing other people.

The words of the President have an enormous weight and ought not to be used indiscriminately.

It would be exceedingly easy to set the country all by the ears and foment hatreds and jealousies, which, by destroying faith and confidence, would help nobody and harm everybody. The end would be the destruction of all progress.

While every one knows that evil exists, there is yet sufficient good in the people to supply material for most of the comment that needs to be made.

The only way I know to drive out evil from the country is by the constructive method of filling it with good. The country is better off tranquilly considering its blessings and merits, and earnestly striving to secure more of them, than it would be in nursing hostile bitterness about its deficiencies and faults.

Amity Shlaes and Matthew Denhart are the editors of The Autobiography of Calvin Coolidge: Authorized, Expanded, and Annotated Edition, from which this article is excerpted.

Shlaes is the New York Times bestselling author of Coolidge, The Forgotten Man, The Greedy Hand, and Great Society. She chairs the board of the Calvin Coolidge Presidential Foundation.

Denhart is president of the Calvin Coolidge Presidential Foundation.

Get the Collegiate Experience You Hunger For

Your time at college is too important to get a shallow education in which viewpoints are shut out and rigorous discussion is shut down.

Explore intellectual conservatism

Join a vibrant community of students and scholars

Defend your principles

Join the ISI community. Membership is free.