J.D. Vance, venture capitalist and author of Hillbilly Elegy, speaks on the American Dream and our Civilizational Crisis....

Solzhenitsyn Explains “Beauty Will Save the World”

The following is excerpted from Solzhenitsyn’s Nobel lecture, given in 1972.

Just as the savage in bewilderment picks up . . . a strange object cast up by the sea?. . . something long buried in the sand? . . . a baffling object fallen from the sky?—intricately shaped, now glistening dully, now reflecting a brilliant flash of light—just as he turns it this way and that, twirls it, searches for a way to utilize it, seeks to find for it a suitable lowly application, all the while not guessing its higher function . . .

So we also, holding Art in our hands, confidently deem ourselves its masters; we boldly give it direction, bring it up to date, reform it, proclaim it, sell it for money, use it to please the powerful, divert it for amusement—all the way down to vaudeville songs and nightclub acts—or else adapt it (with a muzzle or stick, whatever is handy) toward transient political or limited social needs. But art remains undefiled by our endeavors and the stamp of its origin remains unaffected: Each time and in every usage it bestows upon us a portion of its mysterious inner light.

But can we encompass the totality of this light? Who would dare to say that he has defined art? Or has enumerated all its aspects? Moreover, perhaps someone already did understand and did name them for us in the preceding centuries, but that could not long detain us; we listened briefly but took no heed; we discarded the words at once, hurrying—as always—to replace even the very best with something else, just so that it might be new. And when we are told the old once again, we won’t even remember that we used to have it earlier.

One artist imagines himself the creator of an autonomous spiritual world;he hoists upon his shoulders the act of creating this world and of populating it, together with the total responsibility for it. But he collapses under the load, for no mortal genius can bear up under it, just as, in general, the man who declares himself the center of existence is unable to create a balanced spiritual system. And if a failure befalls such a man, the blame is promptly laid to the chronic disharmony of the world, to the complexity of modern man’s divided soul, or to the public’s lack of understanding.

Another artist recognizes above himself a higher power and joyfully works as a humble apprentice under God’s heaven, though graver and more demanding still is his responsibility for all he writes or paints—and for the souls which apprehend it. However, it was not he who created this world, nor does he control it; there can be no doubts about its foundations. It is merely given to the artist to sense more keenly than others the harmony of the world, the beauty and ugliness of man’s role in it—and to vividly communicate this to mankind. Even amid failure and at the lower depths of existence— in poverty, in prison, and in illness—a sense of enduring harmony cannot abandon him.

But the very irrationality of art, its dazzling convolutions, its unforeseeable discoveries, its powerful impact on men—all this is too magical to be wholly accounted for by the artist’s view of the world, by his intention, or by the work of his unworthy fingers.

Archaeologists have yet to discover an early stage of human existence when we possessed no art. In the twilight preceding the dawn of mankind we received it from hands which we did not have a chance to see clearly. Neither had we time to ask: Why this gift for us? How should we treat it?

All those prognosticators of the decay, degeneration, and death of art were wrong and will always be wrong. It shall be we who die; art will remain. And shall we even comprehend before our passing all of its aspects and the entirety of its purposes?

Not everything can be named. Some things draw us beyond words. Art can warm even a chilled and sunless soul to an exalted spiritual experience. Through art we occasionally receive— indistinctly, briefly—revelations the likes of which cannot be achieved by rational thought

It is like that small mirror of legend: you look into it but instead of yourself you glimpse for a moment the Inaccessible, a realm forever beyond reach. And your soul begins to ache. . . .

[…]

Dostoyevsky once let drop an enigmatic remark: “Beauty will save the world.” What is this? For a long time it seemed to me simply a phrase. How could this be possible? When in the bloodthirsty process of history did beauty ever save anyone, and from what? Granted, it ennobled, it elevated—but whom did it ever save?

There is, however, a particular feature in the very essence of beauty—a characteristic trait of art itself: The persuasiveness of a true work of art is completely irrefutable; it prevails even over a resisting heart. A political speech, an aggressive piece of journalism, a program for the organization of society, a philosophical system, can all be constructed—with apparent smoothness and harmony—on an error or on a lie. What is hidden and what is distorted will not be discerned right away. But then a contrary speech, journalistic piece, or program, or a differently structured philosophy, comes forth to join the argument, and everything is again just as smooth and harmonious, and again everything fits. And so they inspire trust—and distrust.

In vain does one repeat what the heart does not find sweet.

But a true work of art carries its verification within itself: Artificial and forced concepts do not survive their trial by images; both image and concept crumble and turn out feeble, pale, and unconvincing. However, works which have drawn on the truth and which have presented it to us in concentrated and vibrant form seize us, attract us to themselves powerfully, and no one ever—even centuries later—will step forth to deny them.

So perhaps the old trinity of Truth, Goodness, and Beauty is not simply the decorous and antiquated formula it seemed to us at the time of our selfconfident materialistic youth. If the tops of these three trees do converge, as thinkers used to claim, and if the all too obvious and the overly straight sprouts of Truth and Goodness have been crushed, cut down, or not permitted to grow, then perhaps the whimsical, unpredictable, and ever surprising shoots of Beauty will force their way through and soar up to that very spot, thereby fulfilling the task of all three.

And then no slip of the tongue but a prophecy would be contained in Dostoyevsky’s words: “Beauty will save the world.” For it was given to him to see many things; he had astonishing flashes of insight.

Could not then art and literature in a very real way offer succor to the modern world?

[…]

Who else but writers shall condemn their incompetent rulers (in some states this is in fact the easiest way to earn a living; it is done by anyone who feels the urge), who else shall censure their respective societies—be it for cowardly submission or for self-satisfied weakness—as well as the witless excesses of the young and the youthful pirates with knives upraised?

We shall be told: What can literature do in the face of a remorseless assault of open violence? But let us not forget that violence does not and cannot exist by itself: It is invariably intertwined with the lie. They are linked in the most intimate, most organic and profound fashion: Violence cannot conceal itself behind anything except lies, and lies have nothing to maintain them save violence. Anyone who has once proclaimed violence as his method must inexorably choose the lie as his principle. At birth, violence acts openly and even takes pride in itself. But as soon as it gains strength and becomes firmly established, it begins to sense the air around it growing thinner; it can no longer exist without veiling itself in a mist of lies, without concealing itself behind the sugary words of falsehood. No longer does violence always and necessarily lunge straight for your throat; more often than not it demands of its subjects only that they pledge allegiance to lies, that they participate in falsehood.

The simple act of an ordinary brave man is not to participate in lies, not to support false actions! His rule: Let that come into the world, let it even reign supreme—only not through me. But it is within the power of writers and artists to do much more: to defeat the lie! For in the struggle with lies art has always triumphed and shall always triumph! Visibly, irrefutably for all! Lies can prevail against much in this world, but never against art.

This is why I believe, my friends, that we are capable of helping the world in its hour of crisis. We should not seek to justify our unwillingness by our lack of weapons, nor should we give ourselves up to a life of comfort. We must come out and join the battle!

The favorite proverbs in Russian are about truth. They forcefully express a long and difficult national experience, sometimes in striking fashion:

One word of truth shall outweigh the whole world.

It is on such a seemingly fantastic violation of the law of conservation of mass and energy that my own activity is based, and my appeal to the writers of the world.

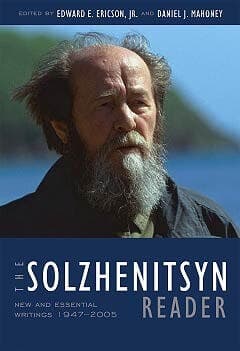

The Russian writer and Nobel laureate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn spent time in the Soviet gulag and pursued the life of an underground writer until he was catapulted to international fame with the unexpected publication of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich in 1962. Get the rest of his Nobel lecture, in addition to his stories, poems, essays, and speeches, in the comprehensive The Solzhenitsyn Reader.

Get the Collegiate Experience You Hunger For

Your time at college is too important to get a shallow education in which viewpoints are shut out and rigorous discussion is shut down.

Explore intellectual conservatism

Join a vibrant community of students and scholars

Defend your principles

Join the ISI community. Membership is free.