The New York Times’s “1619 Project” has renewed debates over the nature of America’s “founding.” Arguing that our whole constitutional system was cast using slavery as its main, if not sole, material, the project’s authors conclude that our polity must be taken apart and remade, or at least set on a new foundation. This kind of argument is not unprecedented: analyses of American origins have almost always served the needs of the present. References to “the Founders” have long been used by those on the left and the right alike to defend their positions in contemporary political and cultural battles. Whoever describes the past shapes the present, and if America was badly or unjustly founded, then exposing those flaws allows a reshaping today in accordance with a new vision.

But what if America was never founded?

Russell Kirk’s The Roots of American Order traced the influence of four cities—Athens, Rome, Jerusalem, and London—on the formation of the American republic. He demonstrated that America’s order did not arise de novo but emerged from a patrimony of thought and the lessons of experience. Political ideas, he argued, are carriers of historical experience and judgments, the residue of hard-won truths gained in the crucible of trial and error. Kirk believed that the unique historical experiences of these four cities created paradigmatic understandings of order that Americans wove together into their constitutional fabric.

His book was written in 1974 in anticipation of the bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence and amid serious political scandal. It’s not a stretch to see the book as motivated by the problem of corruption: not only personal corruption but the corruption of a regime—that is, its systemic decay. How America could avoid the fate of the republics of the past was the central question to which thinkers put their minds during the framing of the Constitution, and Kirk raised that question anew in the shadow of Watergate and Vietnam.

Note the title: The Roots of American Order. Kirk does not evoke some variation of “the American founding,” which, in contrast to the organic metaphor implied in the word Roots, would make America seem more an artifice than an historical development. Kirk wanted to emphasize continuity rather than discontinuity in American history.

His book includes as an appendix a chronology that begins in 2850 BC and ends in 1866 with the publication of The American Republic by Orestes Brownson. One is tempted to see the twelve-page chronology as idiosyncratic—and it is—but its unifying theme is that history is full of contingencies that require sensitive thinkers and “great men” somehow to turn the apparent randomness of circumstance into meaningful action. Kirk draws attention to efforts to snatch back immortality from time’s all-thieving hands. Overseeing all such human efforts, driven as they are by pride and marked by tragedy and irony, stands the watchful eye of Providence, a God who “intervenes” in human affairs and who in the process generates both resentment at his interference with our freedom and rage at not having such interferences result in perfection.

Kirk’s chronology is not intended to be Whiggish, a simple timeline of progress that somehow culminates in American greatness. It is fitful and haphazard, telling a story of achievement and failure, of greatness and meanness, of rise and fall, of things divine tasted partially and things Satanic swallowed wholly, of a Providence whose mysterious workings the finite human mind can grasp only by faith. As Kirk liked to say, paraphrasing T. S. Eliot: there are no lost causes because there are no gained ones.

And that is why the chronology ends with Brownson, a defender of “the permanent things” who understood that no regime or governing authority can sustain itself without some sort of religious sanction. Every living nation, Brownson argued, “has an idea given it by Providence to realize,” which is that nation’s “special work, mission, or destiny.” “The American republic,” he observed, “has been instituted by Providence to realize the freedom of each with advantage to the other.”

Brownson explicitly defended the idea of the nation as “an organism, not a mere organization—to combine men in one living body, and to strengthen all with the strength of each, and each with the strength of all—to develop, strengthen, and sustain individual liberty, and to utilize and direct it to the promotion of the common weal.” In doing so, “the social providence” imitates divine Providence, a continuing act of creation by which all that is human returns to its origin and end.

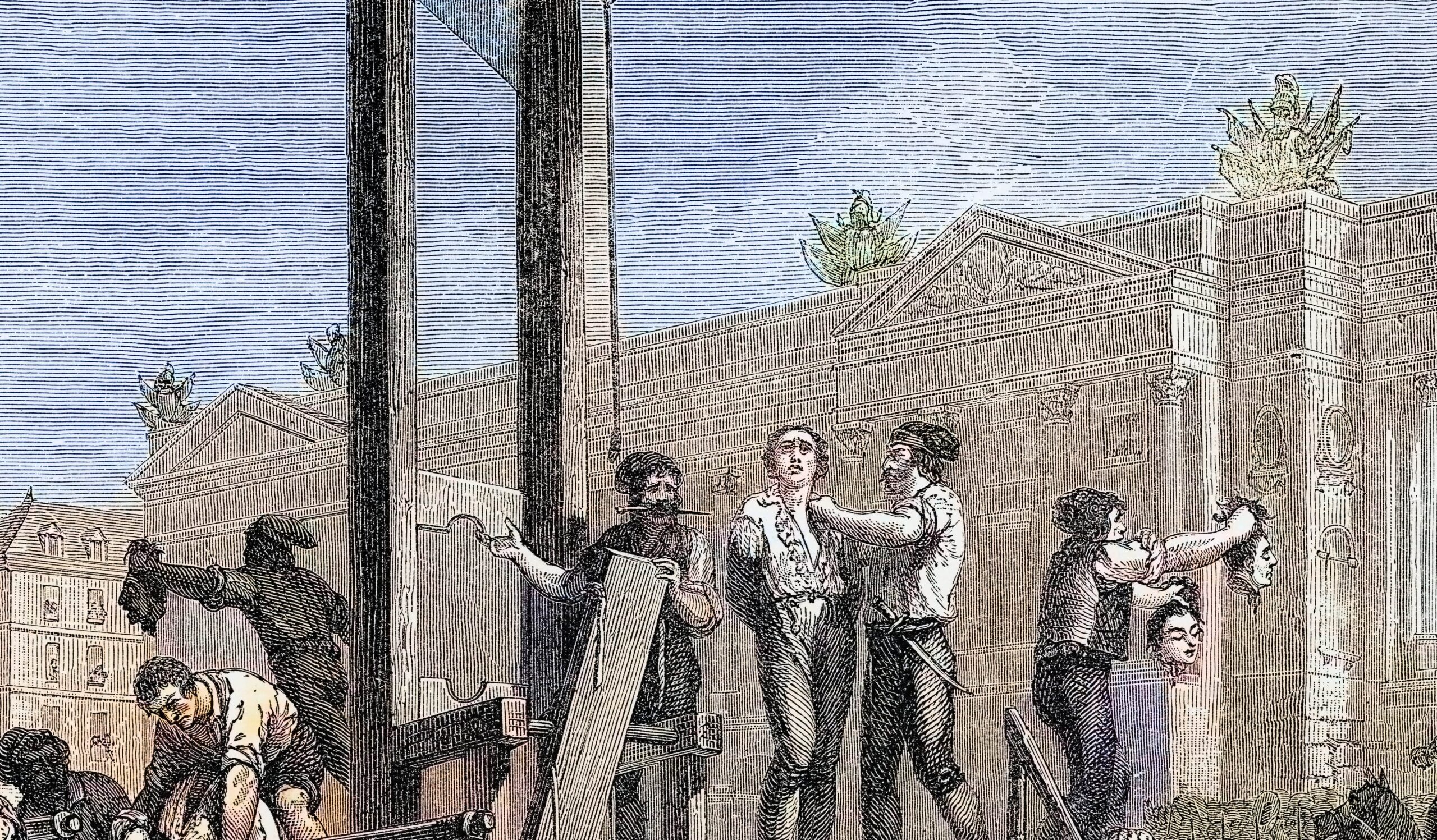

In this sense, America’s roots grow not into a founding but into a constituting. The term founding carries within it not only the idea of establishing but of manufacturing something, in the sense of casting metal: that is, something bound to endure, a metal that doesn’t rust. The great “founders” of political society “founded” in both senses: they laid social life on new and solid foundations, and they also mixed the unformed elements available to them to recast political life into something new and enduring. It was Machiavelli who saw the Prince as operating on the raw materials of political life and forming them, through an act of creative will, into something new.

A political “founding” is artisanship, and the artists are typically tyrants, for violence is the means of such fashioning. Many of history’s great “founders” have the reputation of being tyrants. One of the central problems for political thinking, therefore, is whether a just regime can ever result from unjust origins—namely, the application of violence in accordance with the vision of one person. This problem forms a central concern of Cicero, who postulated the idea of a Golden Age as its solution. We see it as well in Augustine’s City of God, where he resolves the problem by distinguishing sacred history from secular history, the former linear and the latter a cycle of rises and falls.

But a “constitution” is a different sort of thing from a founding. Brownson refers to the former’s “twofold” nature: as a nation or a people and as a government. The formation of a nation is providential, and the government emanates from the nation. Constitutions are developments, not creations; they are generated, not made. They reflect the inner dynamism of a nation’s purpose. The experience of Israel revealed the ethical meaning of a “people” organized in time under the authority of God and his appointed agents, the prophets, who would constantly call the people back to covenantal obligations under the law. Because these obligations carry with them blessings and curses, a people so constituted can be either healthy or unhealthy. (There is an analogy to saying “that person has a strong constitution.”)

Brownson contrasts this view to the thought of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and his obsession with origins. Whether it is the formation of personality, the rupturing of natural comity into emerging sociality, the development of social order, the inculcation of proper virtue, or the location of the self in generative experiences, Rousseau argues that order always results from some sort of founding activity, an authoritative fashioning that determines the subsequent enterprise.

The idea of a “founding” wasn’t itself founded by Rousseau, of course. We see it in the actions of a Solon or a Lycurgus or in Rome’s description of its own origins, and we see it discussed with great clarity in the work of Machiavelli and taken up subsequently through a series of “Machiavellian moments,” wherein political crises require great actors to try to stabilize a regime’s existence. Time is itself taken as the great solvent of political life, but if the regime is well founded, then the corruptions of time may be, if not avoided altogether, at least put into abeyance. Can it be founded, however, without unjust exercises of power and violence?

Rousseau thought not and addressed this problem in chapter 7 of the second book of his Social Contract. While man is born free and is everywhere in chains (a form of metal fastening Rousseau offers as his primary description of social life), the “good” society—one that transcends the give-and-take, the agonism and the friction, of “ordinary” politics—is the one brought into being by a “lawgiver.” This act of “lawgiving” not only re-forms society but reconstitutes human nature itself, which is the only way a society can be formed wherein all machineries of division are melted down and recast into harmonious unity. The Lawgiver has the characteristic of “being able to see all men’s passions without having any of them” and is thus able to form a society independent from the interests of any one particular part of it, the want of which has been the flaw in every prior regime. This is why, according to Rousseau, “the act that constitutes the republic isn’t part of its constitution.” Indeed, the founding act “has nothing in common with human power,” driven as that is by narrow interest, and is in fact “an enterprise that surpasses human powers,” in that it operates “by divine authority.”

From Magna Carta to The Federalist

Is there an American founding in this sense? Some would have us believe so. America, the thinking goes, is a propositional nation, based on universal and ahistorical principles that are instances of divine command and favor. The Founders were men wise and just, who somehow transcended the petty interests of the day. One might even think them demigods. But this is not how Russell Kirk saw it. Regimes, he argued, are not created out of “abstract principles” but develop “out of the circumstances of the times of trouble” within which a people find themselves. Under the most fractious circumstances, leaders will articulate a vision of common life and the common good without which a people will perish. The leader’s charisma makes order possible, and his sin makes constitutional limits necessary.

This helps us to understand better Kirk’s chronology, which reveals the back and forth movements of such articulations. Tellingly, Kirk reflects Brownson’s belief that the vision could not receive greater articulation and clarification than in the American republic. Impressed in America’s DNA is the ancient wisdom of a covenantal people gathered under God to model to the world God’s providential care.

Kirk encourages skepticism that the persons engaged in forming our constitutional system or participating in our war of independence ever thought of themselves as engaged in a founding. Granted, there are counterindications here and there: in some of the letters and speeches of George Washington, for example, arguably in the adoption of the Great Seal in 1782, and in a couple of instances in The Federalist Papers.

In Federalist No. 1, Alexander Hamilton claims that the Americans had to determine once and for all whether the formation of political institutions could result from reflection and choice or would forever be subject to fate and chance. At stake was a particular conception of liberty and the capacity of mankind to control its own destiny. There are other indications that Hamilton believed he was setting politics on a whole new set of principles. In Federalist No. 9, he comments on how the science of politics, like all sciences, has been improved in the modern age: “The efficacy of various principles is now well understood, which were either not known at all, or imperfectly known to the ancients.” The key discovery, “however novel it may appear to some,” was the “enlargement of the orbit within which such systems are to revolve.” In other words, Publius’s epiphany was that republican government was best administered and stabilized on large, heterogeneous scales rather than in the small, homogeneous communities that Montesquieu celebrated.

In Federalist No. 37, Madison admits to “the novelty of the undertaking” of devising the Constitution, commenting that the Philadelphia Convention had attempted to resolve the difficulty of “combining the requisite stability and energy in government, with the inviolable attention due to liberty and to the republican form,” and the “not less arduous” task of “marking the proper line of partition between the authority of the general and that of the State governments.” Still, “a faultless plan was not to be expected.” It is hard enough, Madison writes, for the human mind to discern the workings of nature. How much more difficult is it to discern the proper workings of human institutions? “Questions daily occur in the course of practice, which prove the obscurity which reins in these subjects, and which puzzle the greatest adepts in political science.” These problems were compounded by the contentiousness of the convention, which resulted from disagreements over what was being constituted.

In Federalist No. 38, Madison expresses some sense that the convention engaged in a founding. Every prior effort to establish a government, he begins, had been undertaken not by an assembly but by a single person. Madison reviews the actions of Draco, Solon, Lycurgus, Tullus Hostilius, and Lucius Junius Brutus as “new-modeling” and the laying of a “foundation.” (This is one of the very few uses of the word founding during the constitutional period, almost all of which appear in this sense.) He prudently expresses concern over such an act. “If these lessons,” Madison wrote, “teach us, on one hand, to admire the improvement made by America on the ancient mode of preparing and establishing regular plans of government, they serve not less, on the other, to admonish us of the hazards and difficulties incident to such experiments, and of the great imprudence of unnecessarily multiplying them.”

Clearly, America was not “founded” in the ancient sense. Still, Madison believed the defects of the regime under the Articles of Confederation were sufficiently grievous to justify a recasting of the system, and those who opposed the Constitution as the solution to the problem had to come up with something better. Yet in any case, such recasting, he believed, had to result from popular will and not from the actions of a tyrant.

Madison’s argument draws attention to the fact that the Constitution is a compromise document, and one with a long patrimony. The integrity of that patrimony was a focus of debate between supporters and opponents of the Constitution. Opponents noted that the document was filled with innovations, many of them not justified by experience, practice, or accepted theory. These innovations, they claimed, were taking experimental license with “our ancient liberties.” What was the source of those ancient liberties? John Adams in his 1776 “Thoughts on Government” makes it clear that the main source of republican order was the Magna Carta, a document that predates by some four hundred years the advent of the liberal era. In their clash over ratification, Federalist and Anti-Federalist alike frequently cite the Magna Carta as the originating document from which American constitutionalism evolves.

Indeed, debates over constitutional formation and ratification took place within the context of English legal history going back at least as far as the Battle of Hastings. The development of the common law, more recent articulation of rights going back to the Glorious Revolution, and the conflicts of Court and Country politics in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Britain were far more the issues at stake in the arguments over framing and ratification than were any debates over theory, whether liberal or otherwise. Moreover, the arguments emerged over a largely shared understanding of human nature, and the mutual conviction that it could not be reshaped by political action.

Nature and History—Not Liberalism

The idea of ordered liberty was largely grounded in classical Christian conceptions of human nature. Federalist No. 10 is often cited as evidence for the claim that the American founding is a liberal one. It is indeed the case that Madison detaches interest from a natural political telos in that document, but he does this in the context of how people form themselves into collective entities. Why would people organize themselves politically into groups with other persons unless it was done on the basis of some sort of “common impulse of passion or of interest”? While we might hope that people are motivated by virtue and by love of the true, the good, and the beautiful, we can count on their being motivated by more narrow interests. Nor should we dismiss those narrower interests as necessarily disconnected from what is true or good or beautiful, even if each man tends to be his own judge in such matters. We should expect, for example, that a parent will be more interested in the well-being of his or her progeny than that of someone else’s.

Nor again does Madison appeal solely to self-interest. In Federalist No. 55, he writes: “As there is a degree of depravity in mankind which requires a certain degree of circumspection and distrust, so there are other qualities in human nature which justify a certain portion of esteem and confidence. Republican government presupposes the existence of these qualities in a higher degree than any other form. Were the pictures which have been drawn by the political jealousy of some among us faithful likenesses of the human character, the inference would be, that there is not sufficient virtue among men for self-government.”

In Federalist No. 57, Madison argues that constitutional government requires rule by individuals who seek the common good, and this requires the appointment to office of men of sufficient wisdom and virtue. Rule by the wise and virtuous is also a prominent theme in Hamilton’s contributions, with respect to the presidency in Federalist No. 68 and the judiciary in Federalist No. 78.

The debates at the Philadelphia Convention and at the state ratifying conventions were extensively concerned with the virtue of political leaders and the populace alike, questions of how to grasp and pursue the common good, and how to create a just society, which, as Madison reminds us in Federalist No. 51, is the end and purpose of government: “Justice is the end of government. It is the end of civil society. It ever has been and ever will be pursued until it be obtained, or until liberty be lost in the pursuit.” Why would liberty be lost in the pursuit of justice? While Madison is not a metaphysical skeptic as regards the just and the good, he is an epistemological skeptic. These are concepts, he argues, that are not simple objects of knowing the way that physical objects are, and thus they involve greater degrees of indeterminateness. For example, you and I may both love our children, but that love, though being the same thing, does not attach to the same object, and it may thus become a source of separation rather than union between us, even if the love in each case is identical in its formal properties.

More important, human knowing is never untouched by human depravity: as a good Humean, Madison believed that passion and not reason occupies the driver’s seat in human psychology. And like David Hume, Madison believed that factions—whether they be of principle, interest, or affection—were baked into the nature of things precisely because human beings had competing and contrasting loves, desires, and motivations that were substantively distinct, and whose individuation admitted of moral justification.

And beyond that, more than any of the other virtues, justice is indefinite in both its conceptual nature and its mode of operations. One can be foolish in the exercise of courage—but, in practice, probably not too many times before the real requirements of courage become clear. With regard to justice, however, opportunities for foolishness abound, and given justice’s relationship to coercive authority the consequences of mistakes going uncorrected can be severe. For that reason, concrete experience and humility are better guides to justice than are abstract principles with their sheen of certainty.

Plato argued that our understanding of justice is related to scale, saying that the only way to discern justice in the city is to rescale it to the dimensions of the soul. Madison recognizes that the problem of justice in the society envisioned in The Federalist Papers is going to intensify, inasmuch as Publius’s political theory reimagines republicanism on an extended scale. The fallibility that attends an understanding of justice becomes even more pronounced when politics is scaled up. Precisely because of justice’s indefinite nature, it can actually become a source of tremendous social strife, particularly when human beings organize themselves with others who share their particular (i.e., factional) understanding of what justice is and what it involves. That is especially true when an understanding of justice is connected to a sense of what one is entitled to. The result will be “oppressive combinations,” Madison warned, where the weaker are subjected to the ideological whims of the stronger, who wield power and thus render liberty insecure.

Publius believed that the republics of the past were undone by their tendency to form into self-righteous factions, a defect that arises, as Madison makes clear in Federalist No. 10 and No. 51, from human nature itself. The result was that the republics of the past “have been as short in their lives as they are violent in their deaths.” Strengthening the Union was the way to avoid that outcome in our country. As Hamilton writes in Federalist No. 9:

A FIRM Union will be of the utmost moment to the peace and liberty of the States, as a barrier against domestic faction and insurrection. It is impossible to read the history of the petty republics of Greece and Italy without feeling sensations of horror and disgust at the distractions with which they were continually agitated, and at the rapid succession of revolutions by which they were kept in a state of perpetual vibration between the extremes of tyranny and anarchy. If they exhibit occasional calms, these only serve as short-lived contrast to the furious storms that are to succeed. If now and then intervals of felicity open to view, we behold them with a mixture of regret, arising from the reflection that the pleasing scenes before us are soon to be overwhelmed by the tempestuous waves of sedition and party rage. If momentary rays of glory break forth from the gloom, while they dazzle us with a transient and fleeting brilliancy, they at the same time admonish us to lament that the vices of government should pervert the direction and tarnish the lustre of those bright talents and exalted endowments for which the favored soils that produced them have been so justly celebrated.

The tendency of factions believing themselves to be just to “vex and oppress” those who disagree with them is the main source of tyranny and corruption. The mechanisms of power must be adequate to the task of checking such tendencies in order to protect the proper exercise of liberty and maintain civil peace. These mechanisms borrow from Publius’s understanding of what human beings are: creatures whose tendency toward self-interest and self-deception may overwhelm their capacities for virtue.

But those engaged in a founding will have none of that. Again, Rousseau makes it clear in the Social Contract that the lawgiver who reconstitutes a regime transforms human nature. The lawgiver takes away each individual’s interest and replaces it with “one that is alien to him”—namely, the good of the whole. The individual is subsumed into a “greater whole from which he receives his life and his being.” The act of founding reconstitutes not only the political regime but humanity itself. Man is replaced by citizen. In the scope and force of its application, this is an act of tyranny.

Such acts are antithetical to the American story, which generally sought to preserve individuals in their liberty while maintaining a peaceful civil order as a precondition to a flourishing one. Organic growth requires attendant care. If we hew too closely to the roots, we risk damaging the tree that provides the canopy of meaning and the sanctuary of social peace for our lives. The organic life requires constant ministration, nourishment, and light if it is to grow strong and beautiful. It must resist the winds and storms that threaten to uproot it, even as it inevitably leans and lists in the direction of the pressures that buffet it.

A tree can look healthy on the outside while being diseased on the inside. Tree doctors will tell you that to determine whether your tree is sick you need to examine it from the ground up. Begin with the roots, then the root collar, then the trunk, finally looking up to the canopy. It’s easy to trim away dead branches and think you have done all you need to do. But those whose task it is to attend to the health of the organism have to tend to the roots. In our time, unfortunately, those who argue that America was badly founded wish to uproot our old-growth constitution entirely.

To put it another way, American order has been deforested by generations of ideological fires. The effort to falsify the American experience at the level of theory has now played out at the level of practice, too. In each case, the object is to dismantle the painstaking work done by our forebears and the civilization they nurtured. It was predictable that once the authors of the 1619 Project convinced our elite institutions that the story of America was simply the story of slavery, alienated youth would take that message to heart and to the streets, as we saw in the rampant vandalism and iconoclasm that broke out last summer. If the foundation was wrong, so was everything built upon it; and, if wrong, then in need of destruction. But the metaphor of a founding is itself wrong, and the same tradition that is tainted with injustice is also, and most importantly, the source of its remedy. Our order lives through its roots in the past, tangled as they are, and it cannot survive if they are ripped up.

Jeff Polet is professor of political science at Hope College in Holland, Michigan.